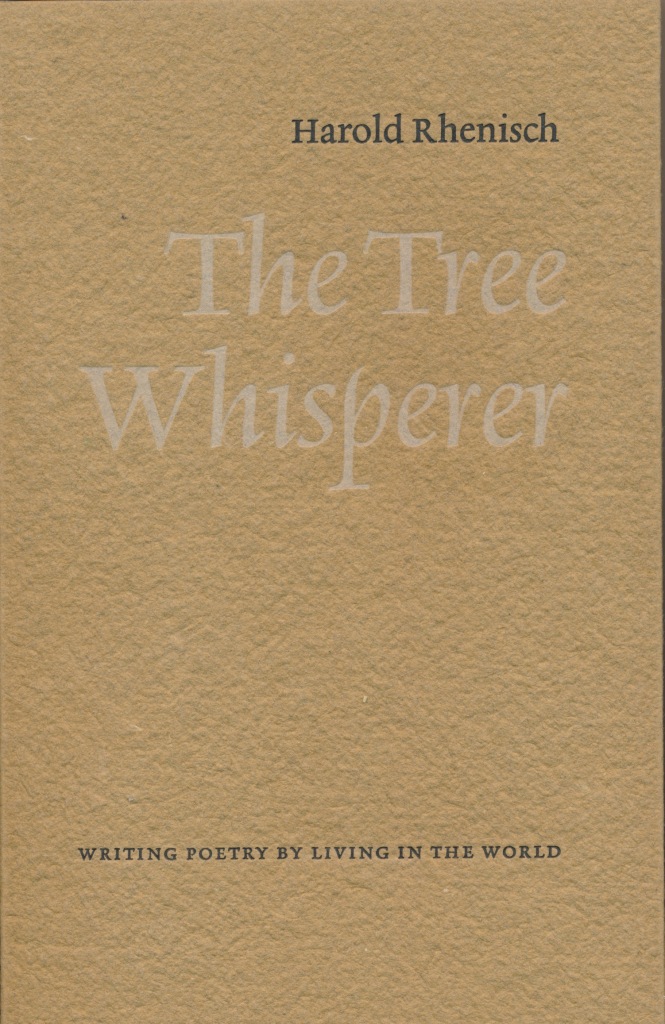

This is a beautiful book, that holds 51 years of my personal tree pruning experience, and a few thousand years of ancestral experience behind it. This hand-made book is just out from Gaspereau Press.

And about 55 years of conversations with my father about trees and the world. This is a book close to the heart. Look at what this blog has given us to share.

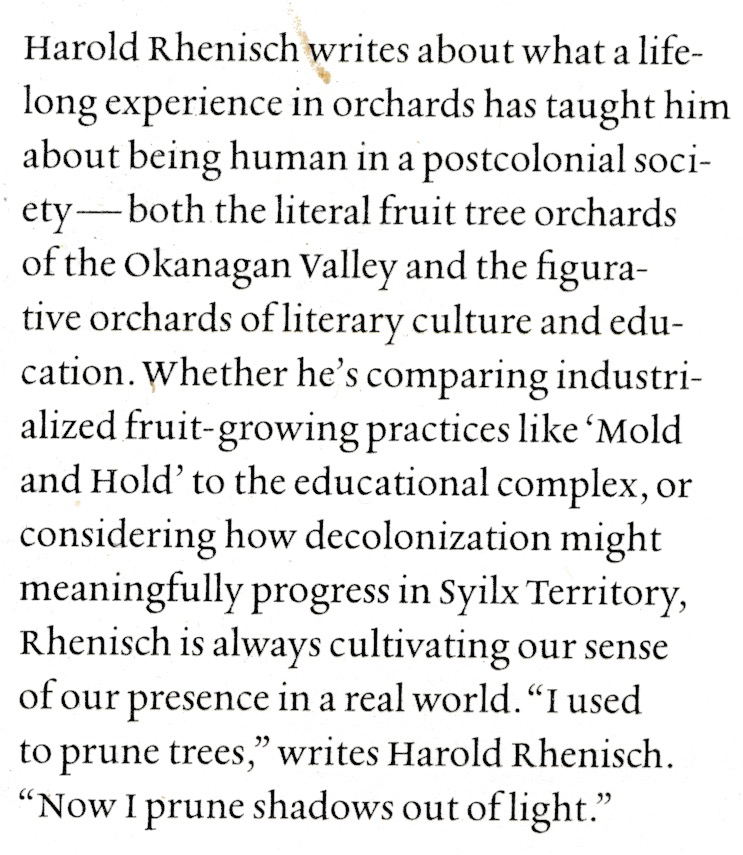

Isn’t that the truth. Fruit tree pruning is not about shaping a tree, nor is it about dominance. It’s about making space for light. One is really making a path for the sun. Trees will follow that. So do I.

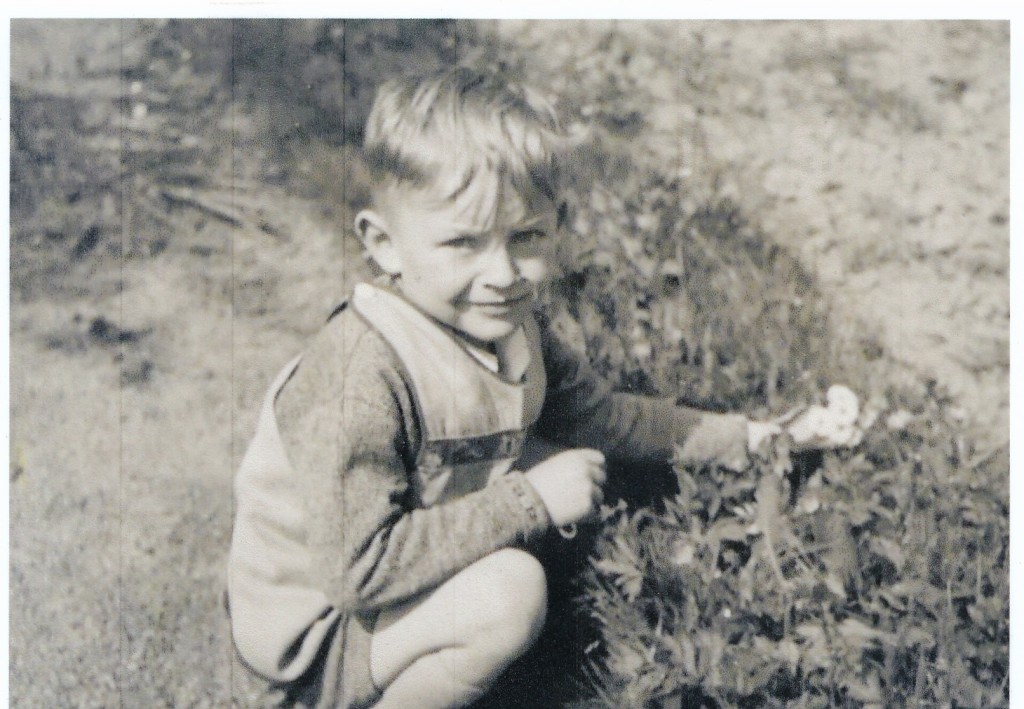

Forty-seven years of poetry are in this book as well, and close to sixty years of experiences with the Earth, as she has raised me and sent me on, from the industrial orchards of my childhood and youth, to my work today, rebuilding lost Indigenous orchards, one graft at a time. This spring, I pruned a transparent apple tree for a bear, even. That was the deal.

years, as bears, horses, human traders, bluebirds…

..and my family, the Leipe’s, the tree people, have brought old knowledge forward into the present.

hem before I learned to write poetry. Unsurprisingly, when I started to write poetry, I was really pruning trees. This book is the story of that path. Its insights into poetry, and tree pruning, come from a deep path, in a sculptural art form in which one must see into the future through the body of another living creature, and work with her to help her thrive.

The Tree Whisperer: Writing Poetry by Living in the World is in the tradition of Henry David Thoreau’s essay Wild Apples, which he wrote after the Battle of Shiloh during the U.S. Civil War in 1862. It was a book about the apples he loved, as is The Tree Whisperer…

Such as grow quite wild, and are left out till the first of November, I presume that the owner does not mean to gather. They belong to children as wild as themselves,—to certain active boys that I know,—to the wild-eyed woman of the fields, to whom nothing comes amiss, who gleans after all the world,—and, moreover, to us walkers. We have met with them, and they are ours. These rights, long enough insisted upon, have come to be an institution in some old countries, where they have learned how to live. I hear that “the custom of grippling, which may be called apple-gleaning, is, or was formerly, practised in Herefordshire. It consists in leaving a few apples, which are called the gripples, on every tree, after the general gathering, for the boys, who go with climbing-poles and bags to collect them.”

Henry David Thoreau, Wild Apples, 1862.

us in this conversation, as you have joined the 153,000 visitors to this blog, because this is a book about the environment, cultural reconciliation, education, poetry, our common past and our common future. In 1937, my great grandfather gave my father a garden …

Hopefully, a long way. You can order The Tree Whisperer from a bookstore, or click on my button on the top of this page and I’ll personally send you a signed copy, with my blessings.