I believe that the writing of the future is here and it is largely present in the world of art writing. I say this in response to the many records of linguistic adventuring recorded in contemporary art writing. It seems to me that readers of art have begun to apply their reading of images to a reading of language, without dropping the Height of the 19th Century language of popular culture. The result is a kind of century-wide gulf that art writers are filling with a cornucopia of undocumented approaches and techniques, while literary traditions are still largely back there before World War I. In one sense, this makes sense: the writers are supplying the background line, on which the art writers are scripting their texts. In another sense, though, it suggests that literary writing will soon be replaced by the new traditions being built up currently and almost out of sight. I think there’s a great opportunity in inserting some dialogue into this divided tradition. On the one side, literary craftspeople supply a pre-modern groundwork, vying to return 20th century literary experimentation to 19th century street ballad populism, such as this:

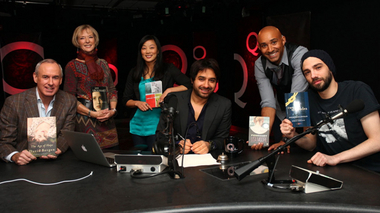

“Canada Reads” 19th Century Redux Populist Debunk-the-Book Event on CBC Radio Source

On the other side, artistic commentators riff off of them into texts that participate in the socializing and de-socializing effects of contemporary art practice. Since the future is being created in this maelstrom of divided roles, my suggestion is that some chat back and forth, in which everyone’s truths can be shared, will lead to a rich, literary future. If such dialogue does not take place, I foresee a future in which the knowledge of the literature of the last century, and all of its powerful engagements during the political throes of the end of the Age of the Book will be lost. I have been reading these magazines for a few years, tracking this new literary genre. Today, an article in Toronto’s C Magazine struck my eye.

Jimmy Limit, Green Liquid with Yellow Bag of Mandarins on Green (…) 2012 Source

Well, to tell the truth, Limit’s image is not the image here. The real image is the magazine, the bar code, the paper it’s printed on, and everything. It is a sculpture.

The words of Stephen Horne’s article, “On the Doing (s) of Art Criticism, are a sculpture, too. He begins with a ritual nod to the current art world practice of preferring processes over objects, and observes…

I’ve been trying to think about what art criticism is, what criticality is — or could be.

Observes is a good word for this kind of thing. It is not that he is thinking. In fact, thinking eludes him, but observation stands in its place. That revelation is worth the price of the magazine alone. It only gets better. Two pages in, we get:

If one admits that there is no “outside,” the terrain becomes more interesting and, paradoxically, less familiar.

Did you observe what is happening there? No thinking, and no meaning at all. In fact, thinking, argument and meaning are not the strategies here. Those are literary strategies. What is important here is observation, and a dance with ritual amulets. Doubt me? Take a look at what happens when the text is gently pushed with some basic literary interventions …

If two admit that there is no “outside,” the terrain becomes more interesting and, paradoxically, less familiar.

If three admit that there is no “outside,” the terrain becomes more interesting and, paradoxically, less familiar.

If four admit that there is no “outside,” the terrain becomes more interesting and, paradoxically, less familiar.

One could, of course, go on. With each of these tiny manipulations, the text reveals the preference given to singular identity, held at the illusion of an objective distance, although there is no distance in a literary object that has not observed its workings beyond the most superficial level. Distance, in other words, is not the goal here, but closeness. The words are being painted, for their emotional resonances and their ability to constrain thought, rather than the literary goals of extending and developing it as part of a tradition. But that probably sounds like gobbledy-gook. Here, visually this is kind of what I mean:

“Pintura Habitada” (Inhabited Painting) ~ Helena Almeida, 1975. Source.

This is more or less what Horne is doing with his words: by laying down quick brush strokes, he defines a reader’s approach to the white page. Almeida was doing it with the white backdrop to a photograph. You could do it with a white canvas, or with something like this (although no blue is involved) …

Signed Building, Kelowna, British Columbia

Signed Building, Kelowna, British Columbia

Take a look at the previous signings that have been painted over by the building’s owners. They are important here.

Just as the building’s owners in the above image have missed the purpose of this art, to claim the public image of the building which inhabits the private space of the person not wishing to be erased by its occupation of space (and thus using indelible pen to leave a trace of his or her own public image, a name), literary readers might easily miss that Horne’s article is not a piece of criticism at all, but a painting, using as a palette a series of resonances. The way in which literature can speak to that is, thus, not in the realm of argument, but in the realm of physical manipulations of the space of the painting (which uses the medium of text and is called “On the Doing(s) of Art Criticism by Stephen Horne.” Again, gobbled-gook. Here, the following should be clearer. First, Horne’s image:

Making suggests a certain way of regarding time: it builds an object, moves from a plan (concept) towards completion and end-product, with the result being a material object that already ‘gives’ a market relation.

All the important social gestures of the art world are there. But look what happens with even an initial treatment of it as text rather than as paint:

Timing suggests a certain way of regarding making: it deconstructs an object and moves to a plan (concept) from completion and end-product, with the result being a market object that already ‘materializes’ a given relation.

Same syntax. Same words, but now the capitalist underpinnings of the approach are revealed more strongly, although very little else of the apparent meaning of the sentence is changed. Meaning is, in other words, a ghost. You can do anything with it that you want, and are not limited to Horne’s approach. Now, in literary writing, this is all a kind of red flag: if the syntax is allowing any meaning to be plugged into the various slots of a sentence, then the writing is just coasting. You could take this to an extreme and get this (which can be completed any way you like, and arrive at more or less the same end, which is predetermined by the syntax):

—— ——– – — — ——— ——: — ———— — —— — —– — – —- (——-) —– ———- — ———-, —- —- ——- – ——- —— —– ——- ‘————‘ – —– ——–.

Some forms of poetry do just that. The thing is, though, that this is a century-old observation. More interesting is that cover to C Magazine. Here it is again:

An Art Object that Is Actually a Magazine Cover

Compare to a book cover. Here’s Lisa Moore’s February, which “won” the Canada Reads verbal boxing match for pop culture literary championship this last February:

Words Are Used to Lead to Image

Words Are Used to Lead to Image

The process of reading entangles word and image.

It’s all designed to catch, rather than enlighten, a reader (although that’s not Moore’s intention, of course, but this is a book, not a manuscript, and it has several faces). Now, here’s another by Lisa Moore:

See how the text has been laid over the image in the same way as the USB code in Limit’s C Magazine Cover?

Now, one more manipulation should make this interesting indeed. I’ll add a text from the High Age of the Book, to show you how much has changed (and stayed the same)…

Now, one more manipulation should make this interesting indeed. I’ll add a text from the High Age of the Book, to show you how much has changed (and stayed the same)…

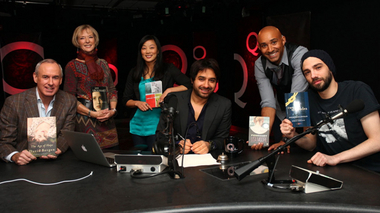

See that? Both types of image represent their underlying syntax, or the technology that they were reproduced by. What’s more, we’re no longer in the age of text, but in an age in which text is image and image is text. Reading is now a visual experience, and the reading of Horne’s essay is also one. In fact, I suggest that his concept of “art criticism” is a form of painting. Rather than creating meaning, he is inhabiting the world that the poets of 1914 were working towards, as they tried to get beyond the limitations of argument. Well, it worked. It started with stuff like this:

See that? Both types of image represent their underlying syntax, or the technology that they were reproduced by. What’s more, we’re no longer in the age of text, but in an age in which text is image and image is text. Reading is now a visual experience, and the reading of Horne’s essay is also one. In fact, I suggest that his concept of “art criticism” is a form of painting. Rather than creating meaning, he is inhabiting the world that the poets of 1914 were working towards, as they tried to get beyond the limitations of argument. Well, it worked. It started with stuff like this:

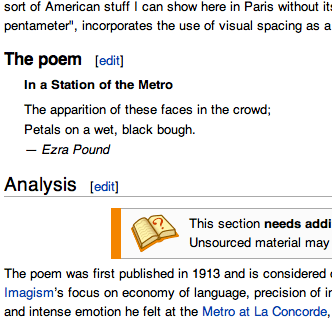

The apparation of these faces in the crowd;

petals on a wet, black bough.

Ezra Pound

Now, that attempt to replace “meaning” by a sudden visual knot, looks like this, in the robotic, populist literary genre called Wikipedia, which represents an attempt to transfer the concept of meaning from the old textual world to the new visual one. Intriguingly, the use of robotic and electronic technology has a big effect, as the writer attempting to “define” Pound’s poem, winds up hectoring and saying banal and irrelevent things..

Still, the splicing work of turning it into a visual object, reveals more than the text did. In this new universe, it is Horne’s approach, and that of art criticism (remember, it is painting, not argument, in the sense of a painter laying down brushstrokes over brushstrokes over time to create an immediately perceivable illusion) in general, which is the most honest. Horne makes a comment which speaks well to this point. Here it is:

Still, the splicing work of turning it into a visual object, reveals more than the text did. In this new universe, it is Horne’s approach, and that of art criticism (remember, it is painting, not argument, in the sense of a painter laying down brushstrokes over brushstrokes over time to create an immediately perceivable illusion) in general, which is the most honest. Horne makes a comment which speaks well to this point. Here it is:

If ‘waiting’ is conventionally understood to be passive while ‘doing’ is active, the space that is art disrupts the binary in favour of a space that is in play.

Applying a literary manipulation (an active reading, in the sense of the Creative Writing school that Robin Skelton tried to start in Victoria in 1967, in which creative response was the communication, not intellectual analysis … a bit before his time, he was) to that text-image, we get:

If ‘writing’ is conventionally understood to be passive while ‘painting’ is active, the space that is art criticism disrupts the binary in favour of a space that is in play.

And that’s pretty much what Horne is doing. One can go further:

If ‘writing’ is passively understood to be conventional while ‘painting’ is active, the space that is art criticism disrupts play in favour of a binary that is in space.

It means the same thing. In other words, meaning is not the issue. Criticism like this could be presented in a gallery setting, as a kind of variation on a theme, so popular back in the days in which painting and art were mostly synonymous, before art moved into reading. It could, however, also be presented in a book, and what is a book but a gallery space, or a theatrical space unfolding in time. And what’s that, but a sculpture? Here’s one:

Alley, Kelowna, British Columbia

Alley, Kelowna, British Columbia

Note the painted-over graffiti on the right. No, you an’t see it, but the grey paint reveals that somewhere, deep down, it is there. Keep that grey paint in mind as you read on.

Do you see? This photograph is a sculpture of time and space. It has been selected by the eye (mine), which has recognized a conjunction forces, in the syntax laid down by a machine meant to mimic the human eye: a camera. A camera is a creator of human spaces. The human who operates that machine is sculpting them, out of a flow. As long as it flows, it’s not time or space, not in the new visual understanding that Horne lives so well within. Now, there’s a lot more to be said about this intriguing photographic space, but I think one more image will do for this introduction to the future.

Alley, Kelowna, British Columbia

Alley, Kelowna, British Columbia

The many layers of concrete, plaster, signage, brick, windows, and so on, on this wall are no different than the work of a sculpture or of a painter on canvas, or of Horne, who uses words in their place. Even the building owner who tried to assert ownership over the public image of his back wall by painting it with grey paint, was living within this visual universe. Only the art critical writers, like Horne, have found the language that speaks to this new world, of a new century. That’s where the literary spark has gone now. Fortunately, for those skilled in words, in a textual sense, there is much that literature can add to this new genre. There is much good work that we can do together. I, for one, am working on it by creating books that work as photographic-textual sculptures that unfold in space and time. They’re not written; they’re sculpted, as are blogs, such as this.