Icelandic is a beautiful language that rolls around in the mouth like pebbles in surf, but it is a little hard to absorb all at once. Let me show you the solution I found in my new book Landings, but first, so you can experience the dislocation of a language at once familiar and strange, here’s some Icelandic, complete with Microsoft’s error warnings:

And a photo to go with it, way off in the East Fjords, which is as far from Reykjavík as you can get before you start swimming to Scotland:

So, that’s nice, right?

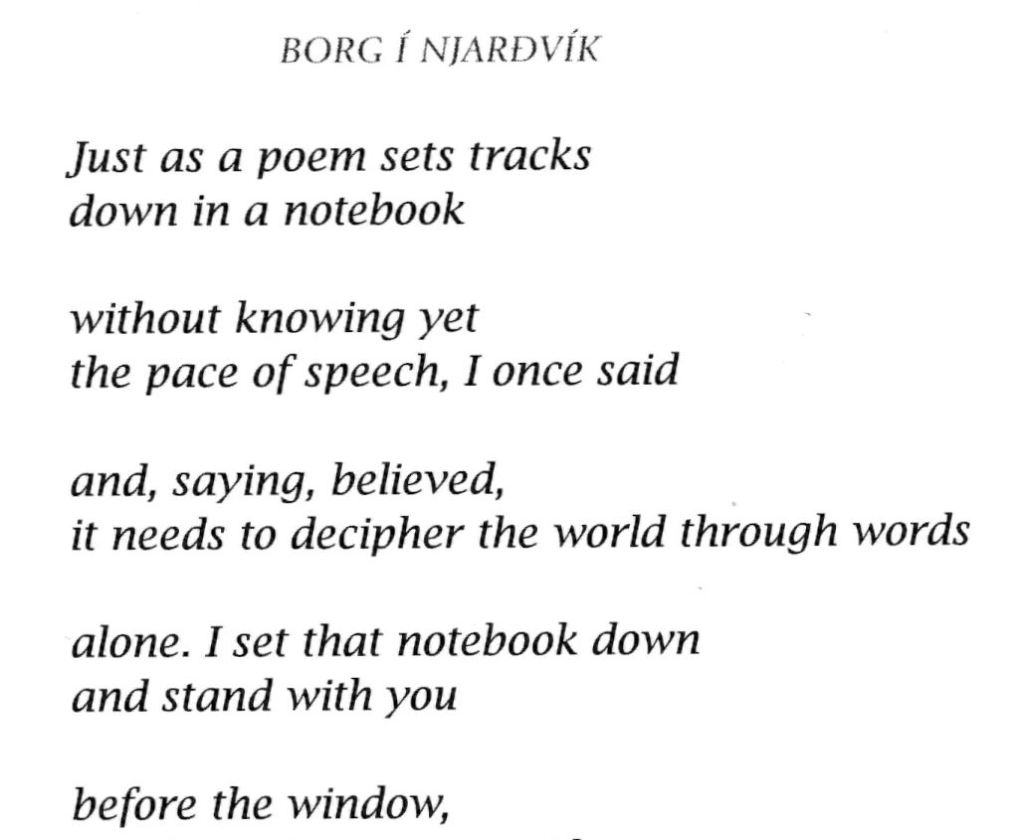

Here’s the info in that wayward dialect of Icelandic now called English:

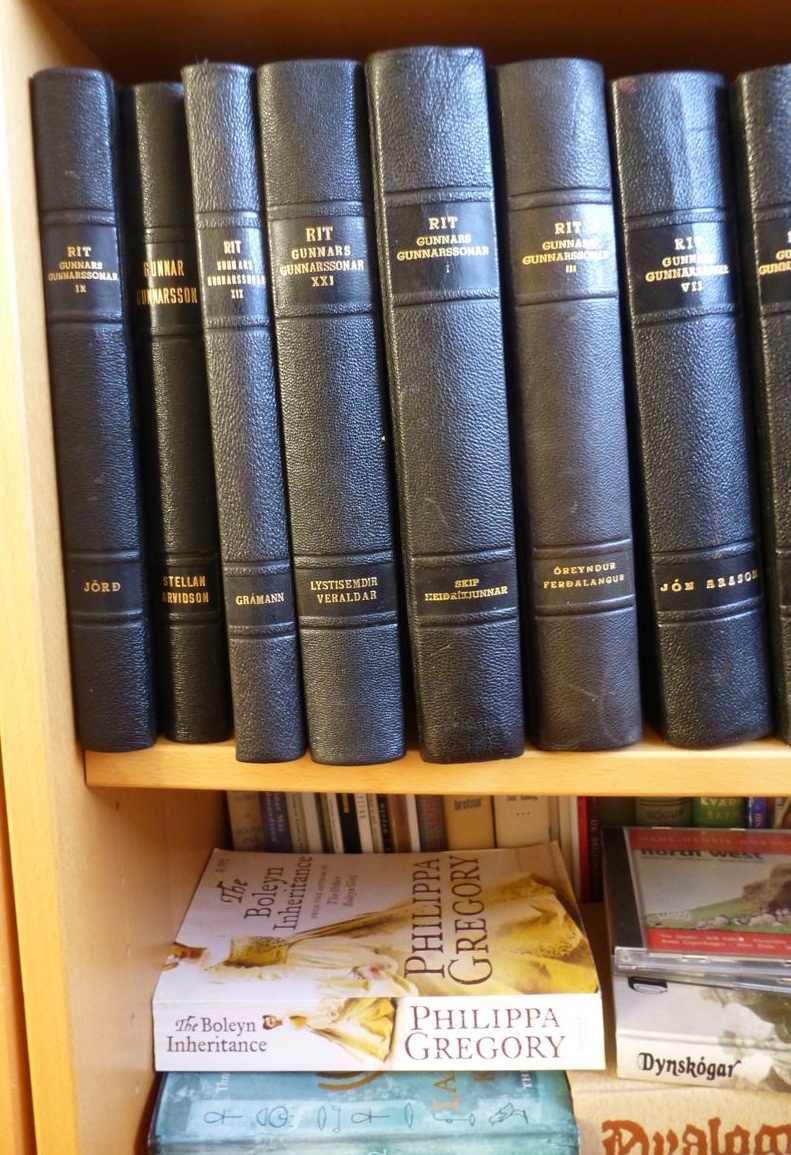

Microsoft is still coughing a little out in its Seattle suburb, but you get the drift. But what if you’re doing this up the next fjord, in a little room at the novelist Gunnar Gunnarsson’s house, a kind of stone novel on an old monastery site…

…where you’ve been alone with Icelandic books for weeks…

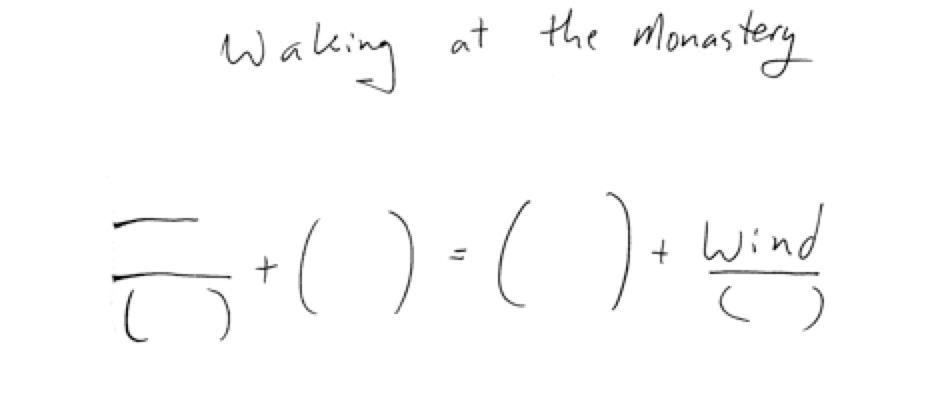

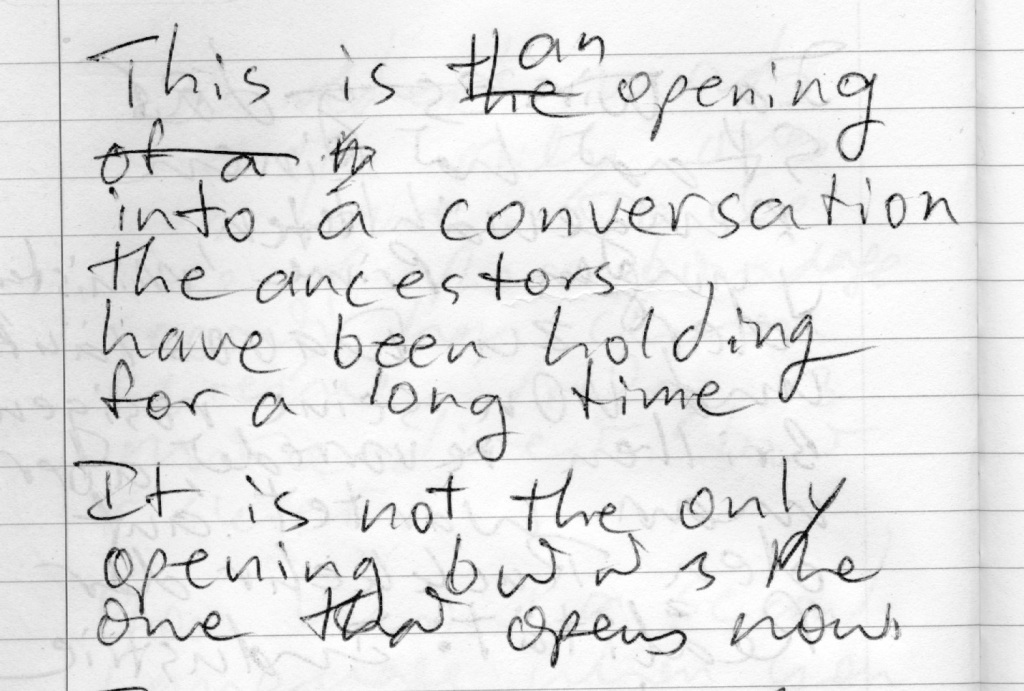

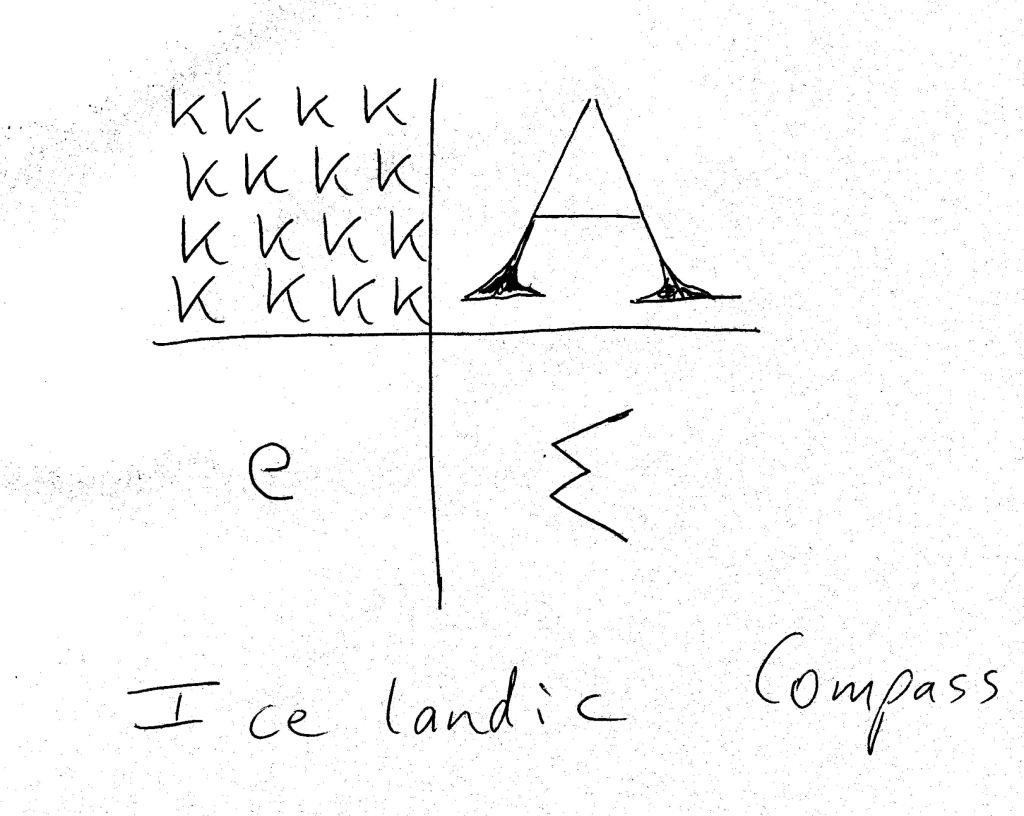

…and have been wind-blown all day? What then? I was just too tired for words in any language, so I tried mathematics instead, on the principle that math is music:

So, wind at any rate! There were ravens.

There were always ravens.

In many countries, they are birds, but in Iceland ravens are Thought and Memory, the capacities of human consciousness that create Mind and Consciousness, except here they are out in the world, not within human selves alone.

Oðinn did that by throwing his eye into the pool at the bottom of the world and getting, surprise!, the ravens as a replacement.

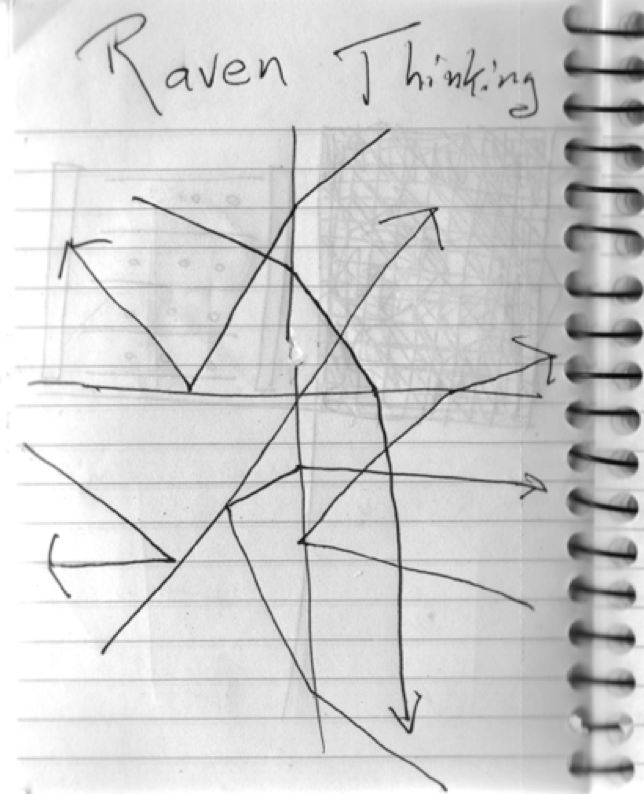

So, what to do with that? What started as an experience with no words had become the experience of having no self, or having the Earth as one! How do you share that? Well, I gave it a go, using the poetic form of a quickly sketched compass, the same four-part shape that was used as an oral map of Iceland 1100 years ago (and today):

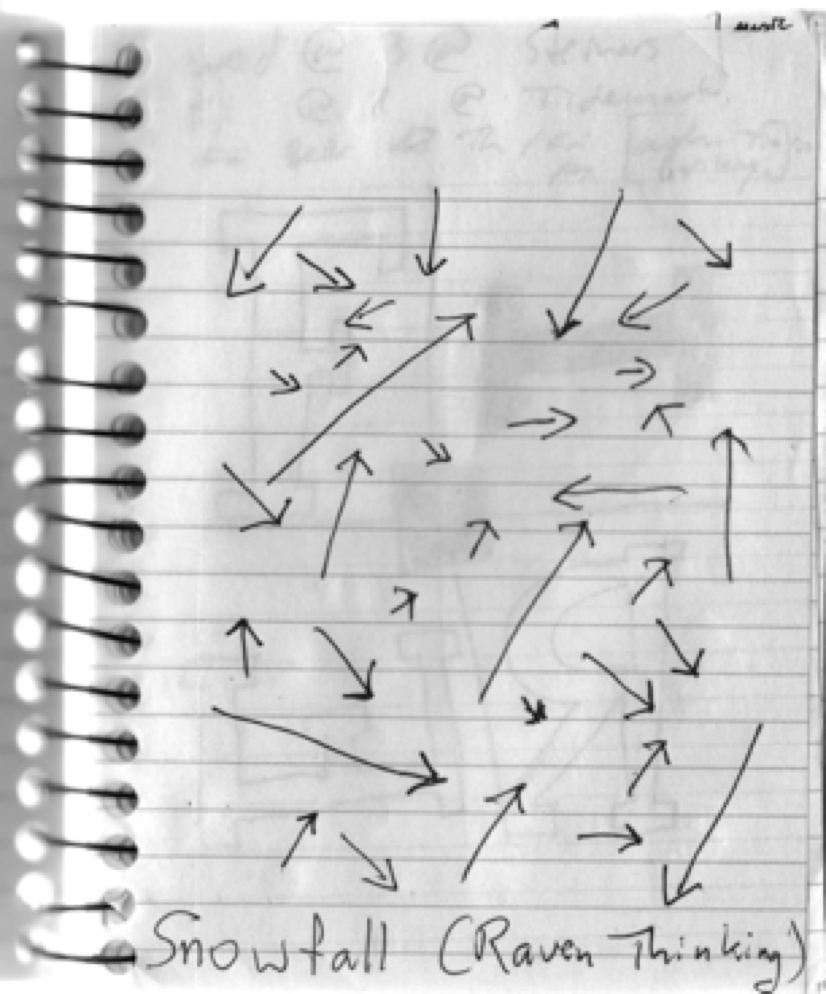

Well, that was fun, so I turned the page. After all, it had started snowing outside…

… with big wet flakes coming down sideways and swirling around any building that blocked it:

It went on like that for days, with the raven tracking me up the canyon in case a) I dropped a sandwich, b) slaughtered a sheep or c) lost my footing and became lunch…

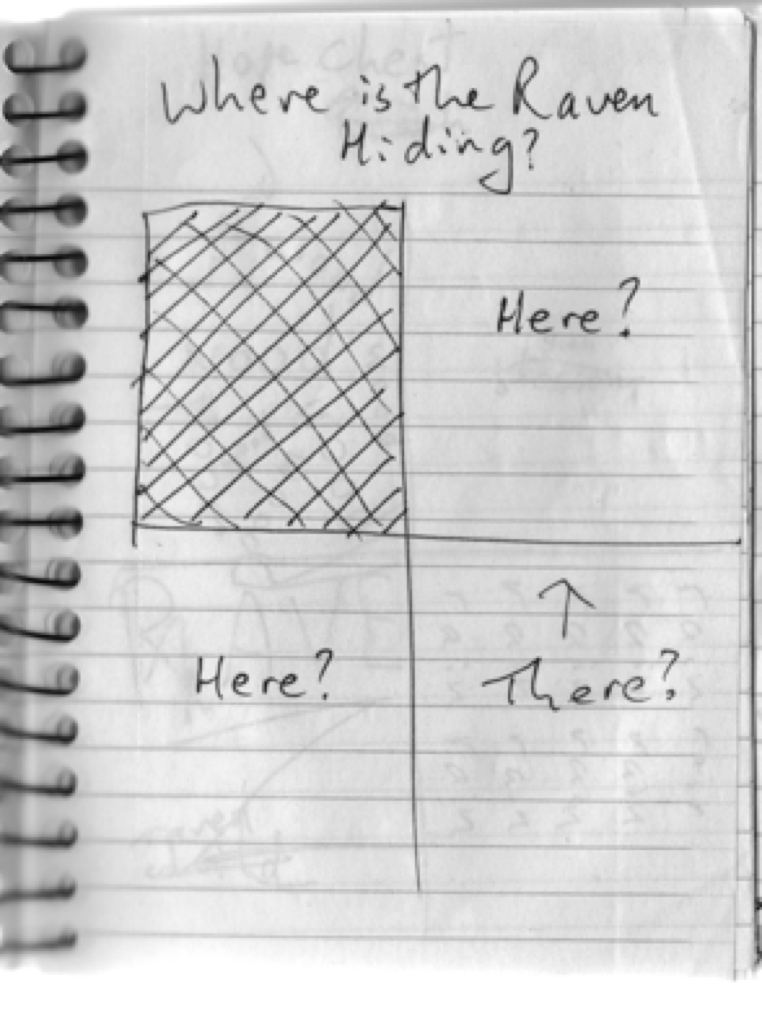

… and exhausted at night, full of a language I could only understand peripherally, but which was taking over my mind and settling it out in a new shape. Eventually, it became a game of Where’s the Raven Now?

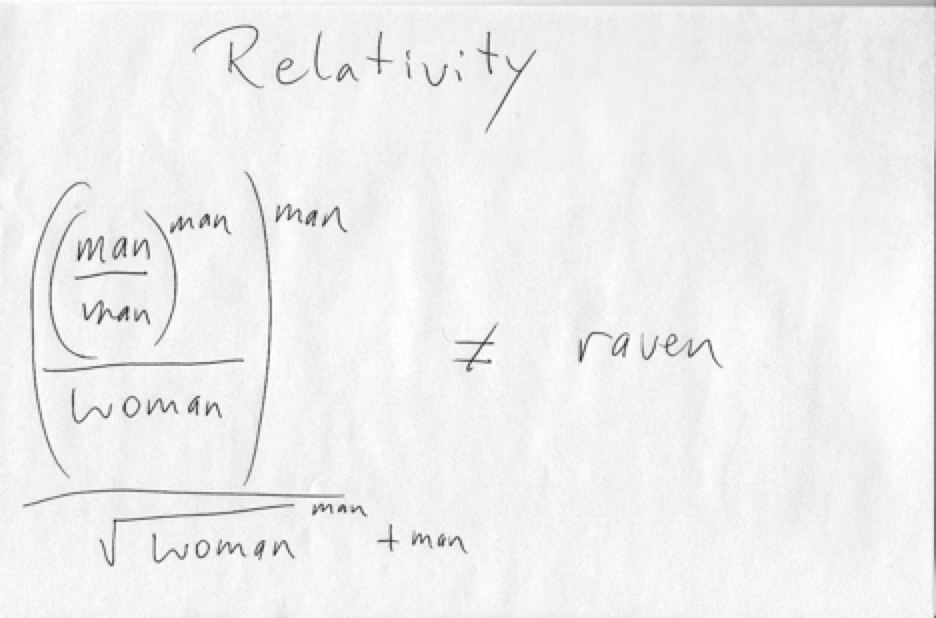

The answer was in plain sight, of course, but had to lead first to its natural conclusion through the path of self-negation. So, you guessed it, more math, like this:

And I left it like that. My time in Iceland had run out. Still, I came back three years later and this time, in my exhausted evenings, travelling around the country, I wrote poems in words (of all things!) at night and, look at that, essentially they were the same poem as the visual artifacts from the trip before, except my English had become closer to Icelandic, elemental, like this:

There’s more than one way to poetry. Some, like this, lead away from poetry to the world, and find their mind, and self, there. It’s a place almost wordless, as Icelandic began for me, but not quite. Physical things are words there, just always on the edge of understanding and quickly flying beyond it into presence, not just of those living today but of those who have woven Earth and words for a thousand years and more. Here’s how I first put after I came home, if one can even leave such a place to go to another:

Photographs can’t quite pull this weaving off, but poems can, because they’re written by reader, writer and Earth at the same time. The path we walk today, whether it’s across a mountain’s back or through a poem, stretches back generations.

Such is reading a poem, too, especially with poems like those in Landings, which are the Earth and a compass at the same time…

… waking together as an island and an eye.

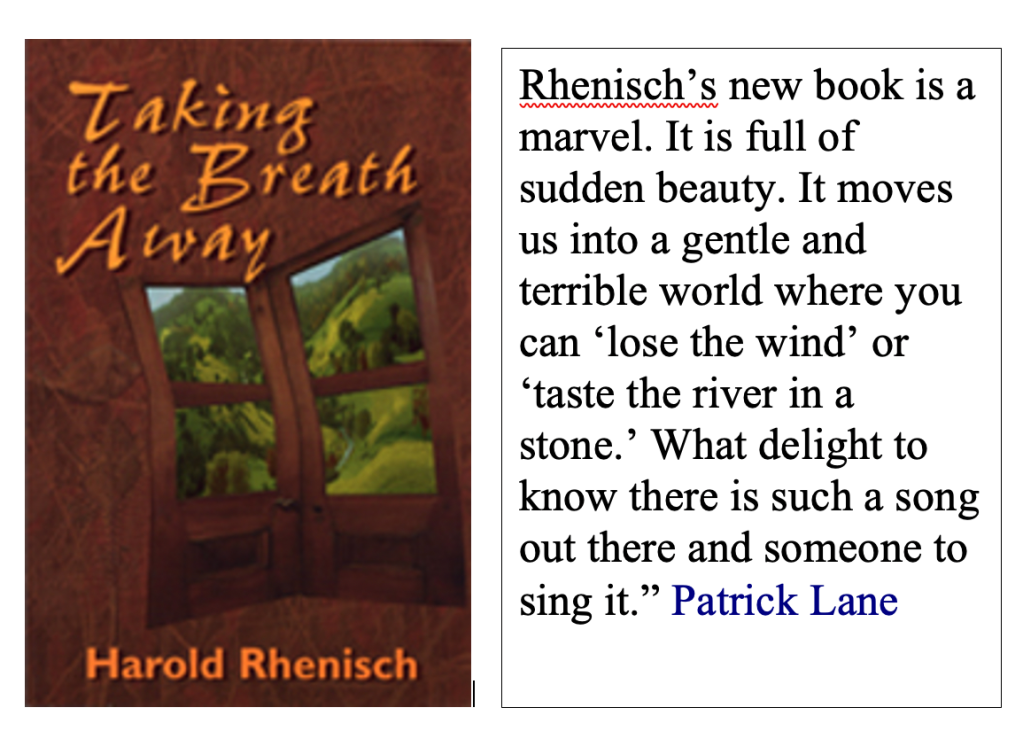

Until the New Year, if you buy a copy of Landings, I will throw in a free copy of my book of German travel poems, Taking the Breath Away, for $30, postage included in Canada. That’s a $48 value. As the poet Pat Lane said of Taking the Breath Away

Landings: $20 + Postage $14 + Taking the Breath Away $14 = $30.