The Tree Whisperer and the Rose

A rose is a twig, a thorn, a leaf, a stem, a seed, seed fluff, bark, root, bud, wood and scent, and now, in early winter, the fruit. This is not, however, a period of fruition. Rather, it is an opening. The opening includes a bird dropping a seed, a seed leaf, a first root and stem and eventually a thorn, and a flower, opening as an invitation, sending its scent across the air to attract a bee or a beetle or a wasp. If a bird didn’t take the answering insect away and the flower was pollinated, the rose answers it back with a seed and the swelling of the stem around the seed. That swelling is the fruit, bright red to call birds out of the midwinter air. It is not that time yet, but in late January, when the fruit is fully ripened by the cold and the warming sun between a new moon and the snows of a full one, a bird will come, eat the fruit and drop the seed, multiplying the opening of the rose. There is no beginning here and no end, only bird and rose calling out and answering together, not with language or intent but with bodies that fit into each other like a leaf into the air. In human terms, that is, in effect, what poetry is, this opening in the world and this opening in the world again. It is not a text.

It is not the following, which is how the Ministry of Education looks on the lives of living things:

Despite the Ministry’s insistence, texts aren’t primary. The text no more starts a process of opening than does an intent. Communication does not begin with a self, a will or a human wish. The body in the world comes first. I, for one, learned to read the world before I learned to read books, and learned to prune fruit trees before I learned to write poetry. When I came to writing poetry, I treated it as a tree, a living thing I was in partnership with. It is not the usual path, but it is a human path. Here’s an example of the first book I read:

I read them as shapes in the darkness of my body and maps of the world. They are. You can read more about these ponderosa pines (for such are those shapes of bark) here, in Ponderosa Pine’s World, and here, in The Tree at the Heart of a People, and even here, in Humans and Pines are One. You can also read about them in my new book The Tree Whisperer, where this whole story is told and the consequences of the B.C. Ministry of Education’s inability to set its settler culture aside and to inhabit the land and people it lays claim to are explored in depth. This matters. Like a rose, it is blossom, bark, stem, wood, root, branch, bud, seed, fruit, and bee in one, and bears, too, which made the apples for us.

It’s a love story. You don’t tell a lover that your love is a text. For that, you’ll get stung. And apples, by the way, are roses. And, yes, these flowers are in the book, and stories of teaching people to learn to prune these trees by recognizing that these wooden bodies and ours are one, and trusting that knowledge. The book demonstrates how.

It is an opening that has been ongoing for 50,000 years, 10,000 of them including humans. I invite you to set this text aside, which is only an invitation and a record of fifty years of opening and join this ongoing opening at a bookstore near you, or here: https://okanaganokanogan.com/harold-rhenischs-shop/. Touch like this is what we do for ourselves on this Earth. It’s not school.

A Path to Poetry When You Have No Words and Then Find Them

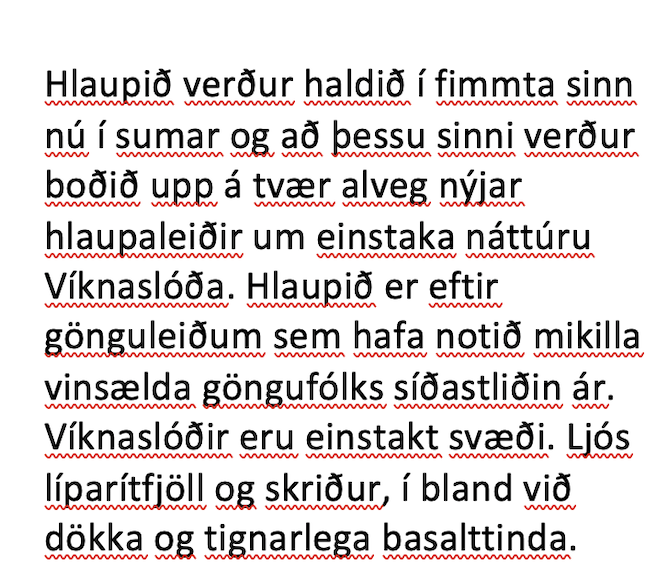

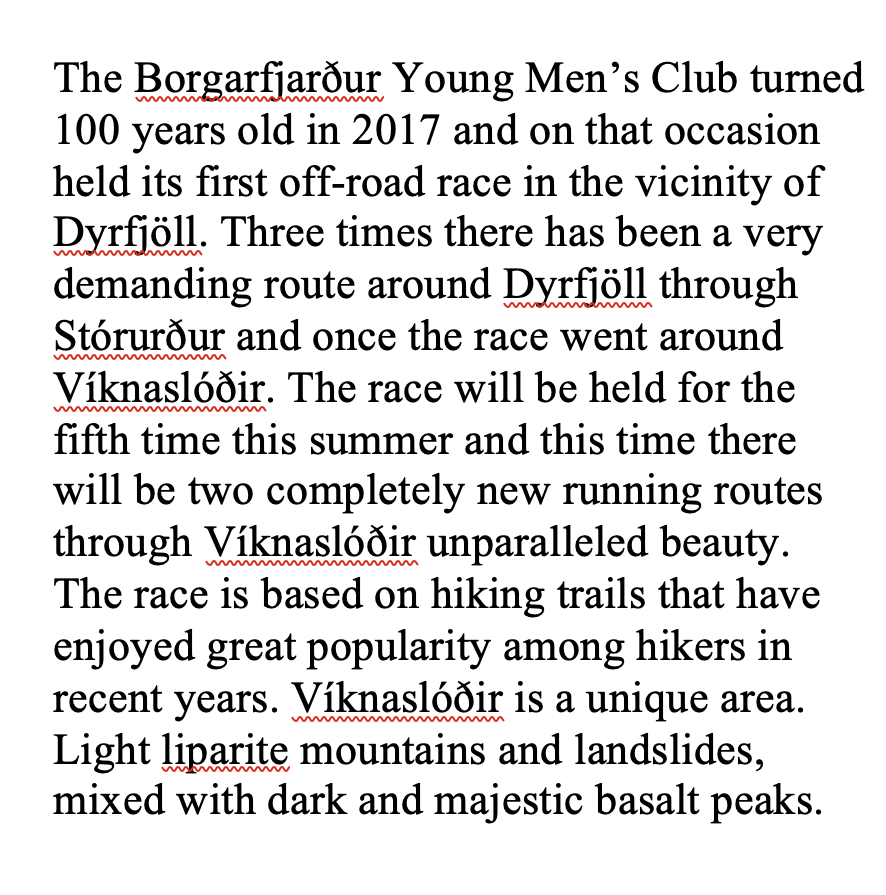

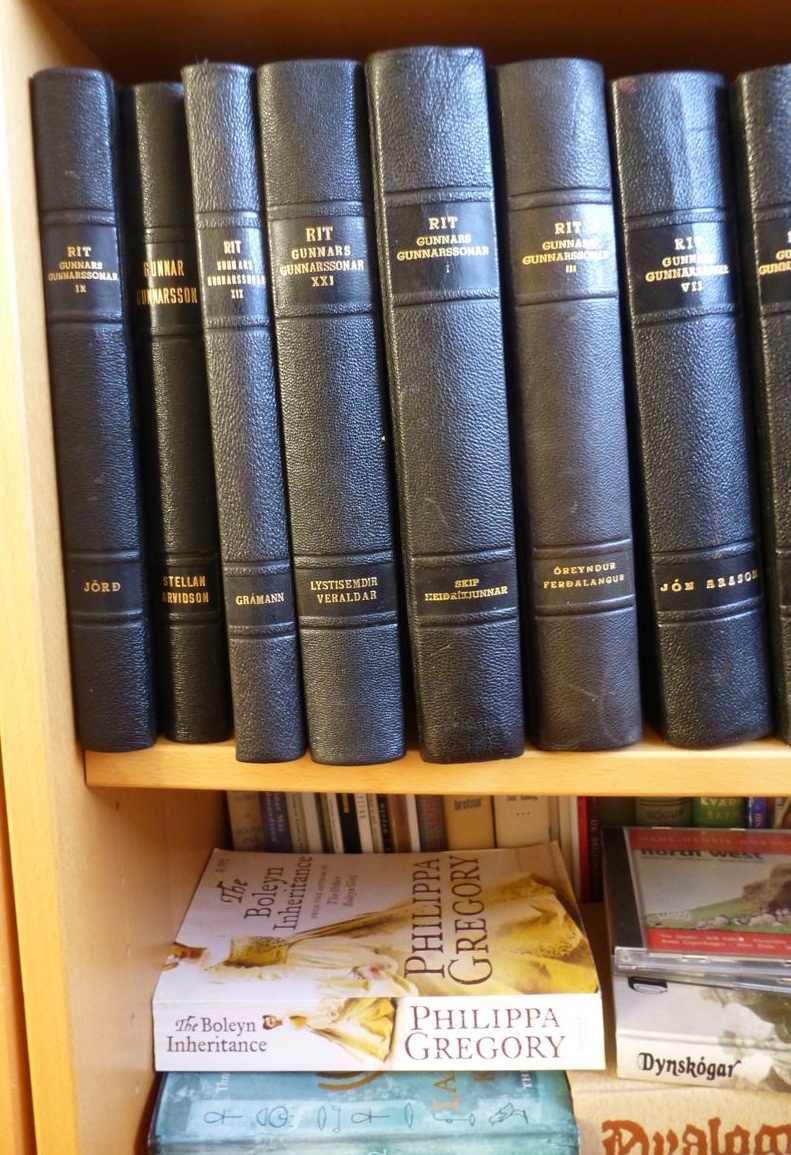

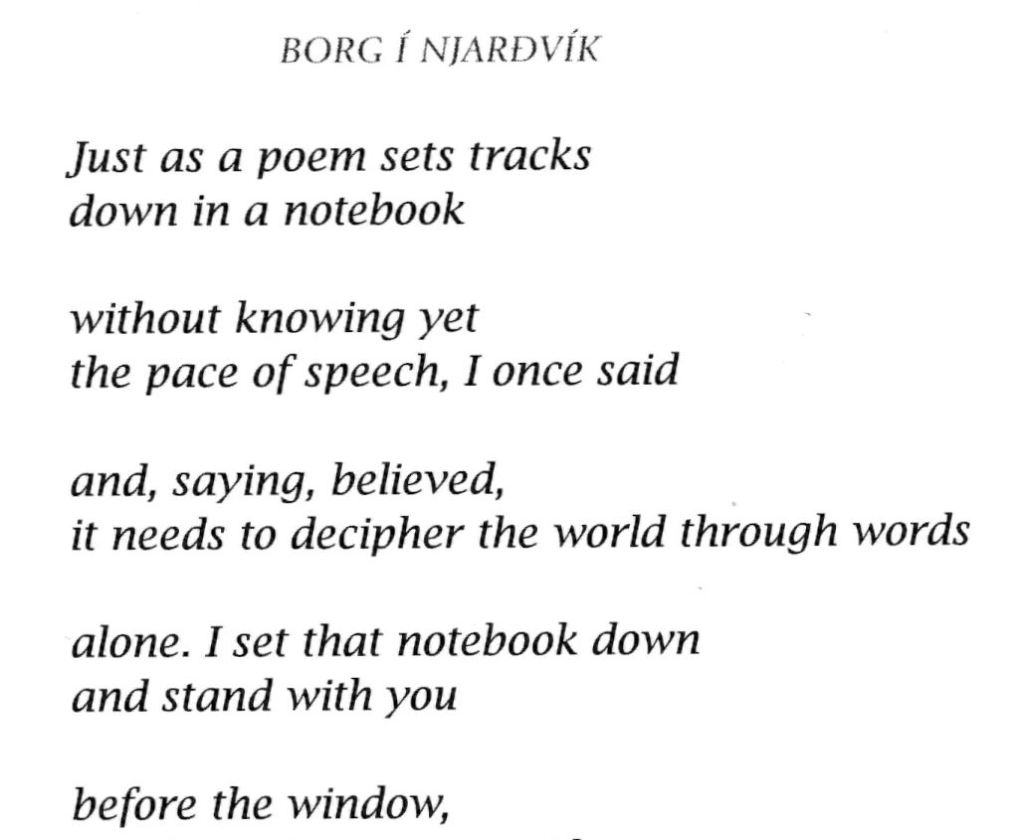

Icelandic is a beautiful language that rolls around in the mouth like pebbles in surf, but it is a little hard to absorb all at once. Let me show you the solution I found in my new book Landings, but first, so you can experience the dislocation of a language at once familiar and strange, here’s some Icelandic, complete with Microsoft’s error warnings:

And a photo to go with it, way off in the East Fjords, which is as far from Reykjavík as you can get before you start swimming to Scotland:

So, that’s nice, right?

Here’s the info in that wayward dialect of Icelandic now called English:

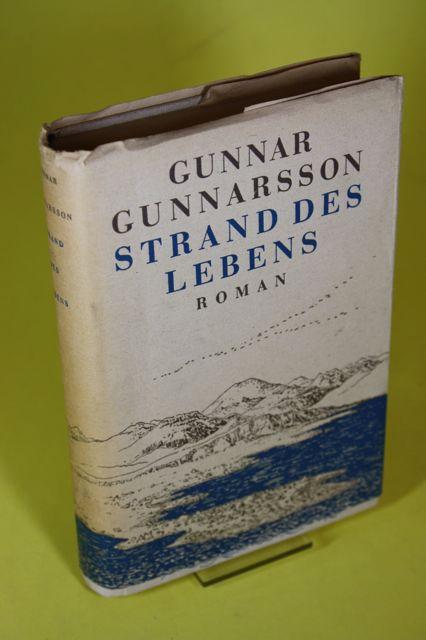

Microsoft is still coughing a little out in its Seattle suburb, but you get the drift. But what if you’re doing this up the next fjord, in a little room at the novelist Gunnar Gunnarsson’s house, a kind of stone novel on an old monastery site…

…where you’ve been alone with Icelandic books for weeks…

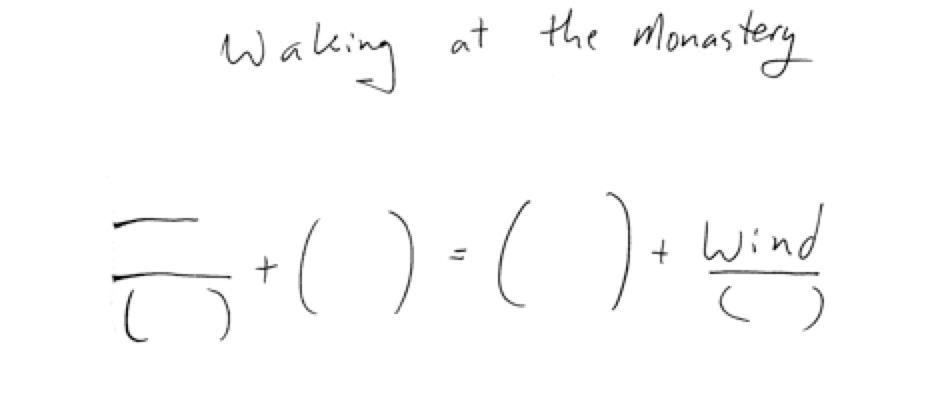

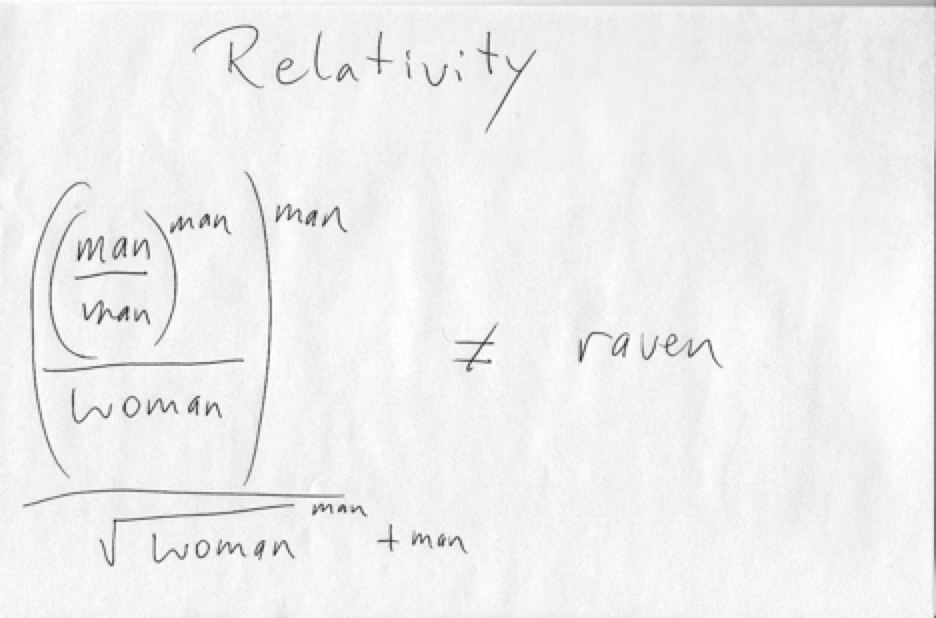

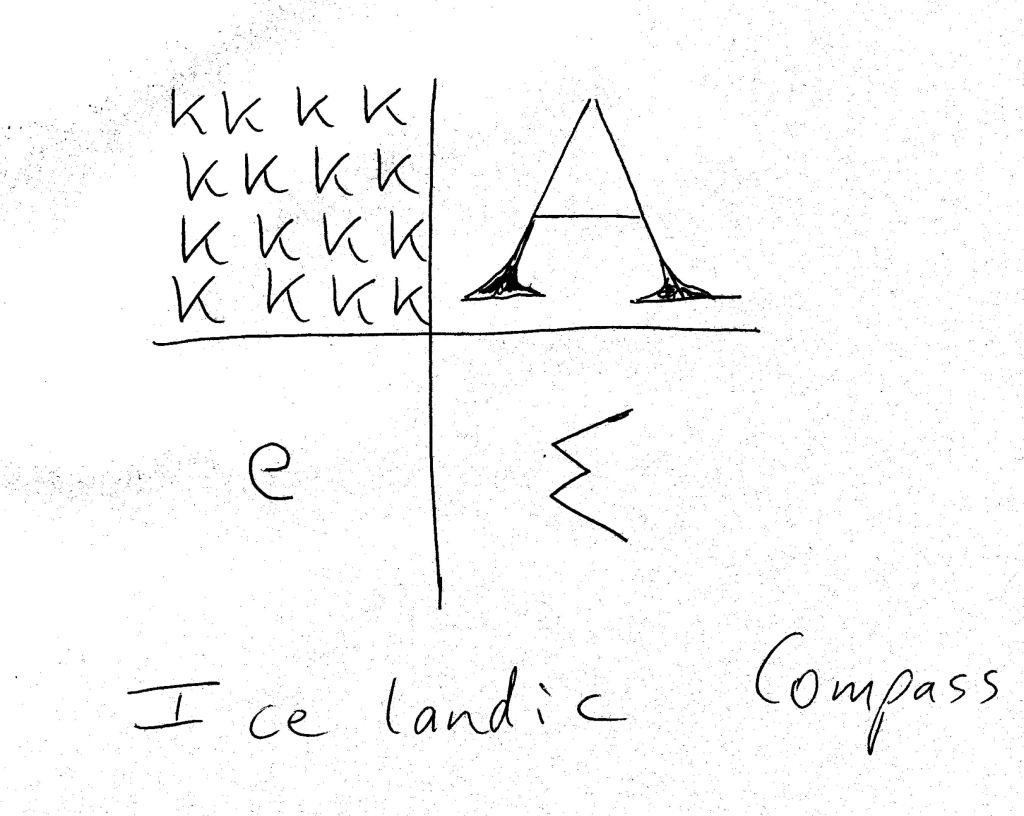

…and have been wind-blown all day? What then? I was just too tired for words in any language, so I tried mathematics instead, on the principle that math is music:

So, wind at any rate! There were ravens.

There were always ravens.

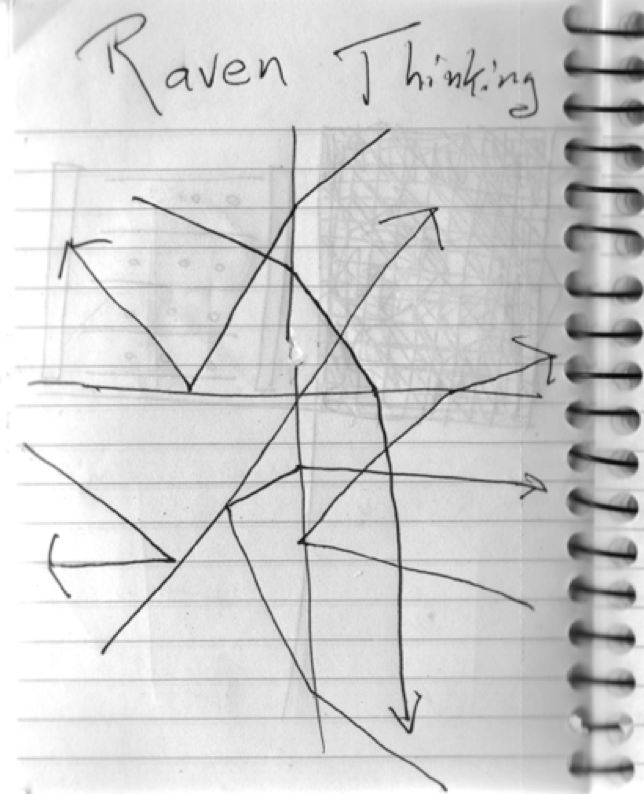

In many countries, they are birds, but in Iceland ravens are Thought and Memory, the capacities of human consciousness that create Mind and Consciousness, except here they are out in the world, not within human selves alone.

Oðinn did that by throwing his eye into the pool at the bottom of the world and getting, surprise!, the ravens as a replacement.

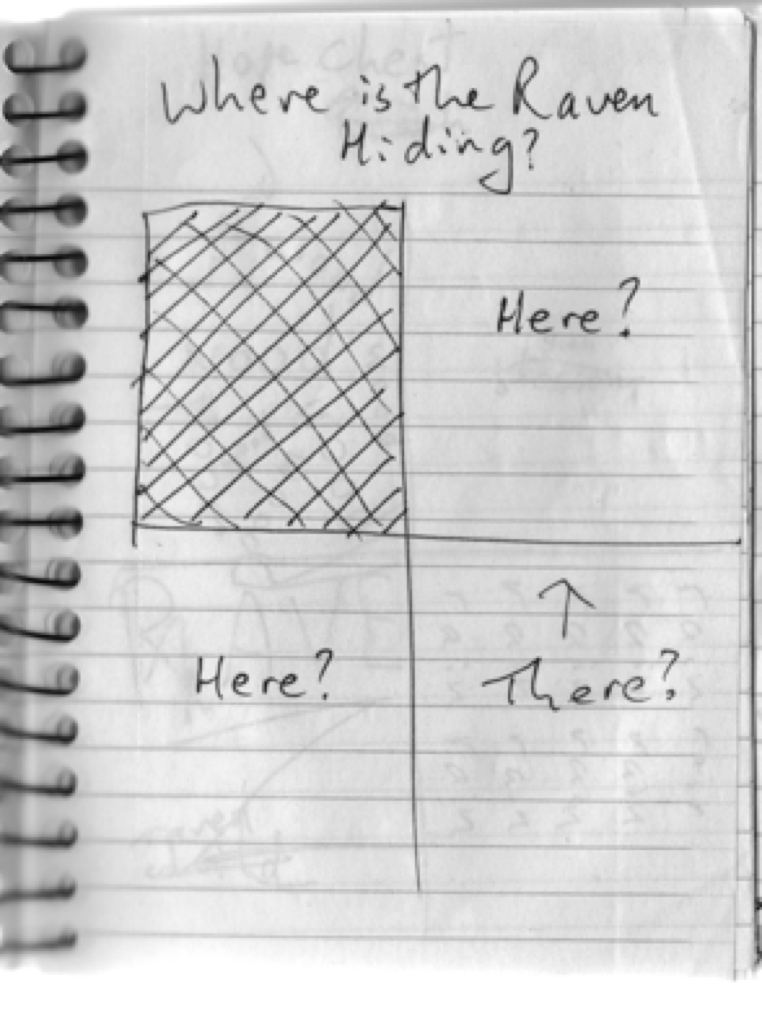

So, what to do with that? What started as an experience with no words had become the experience of having no self, or having the Earth as one! How do you share that? Well, I gave it a go, using the poetic form of a quickly sketched compass, the same four-part shape that was used as an oral map of Iceland 1100 years ago (and today):

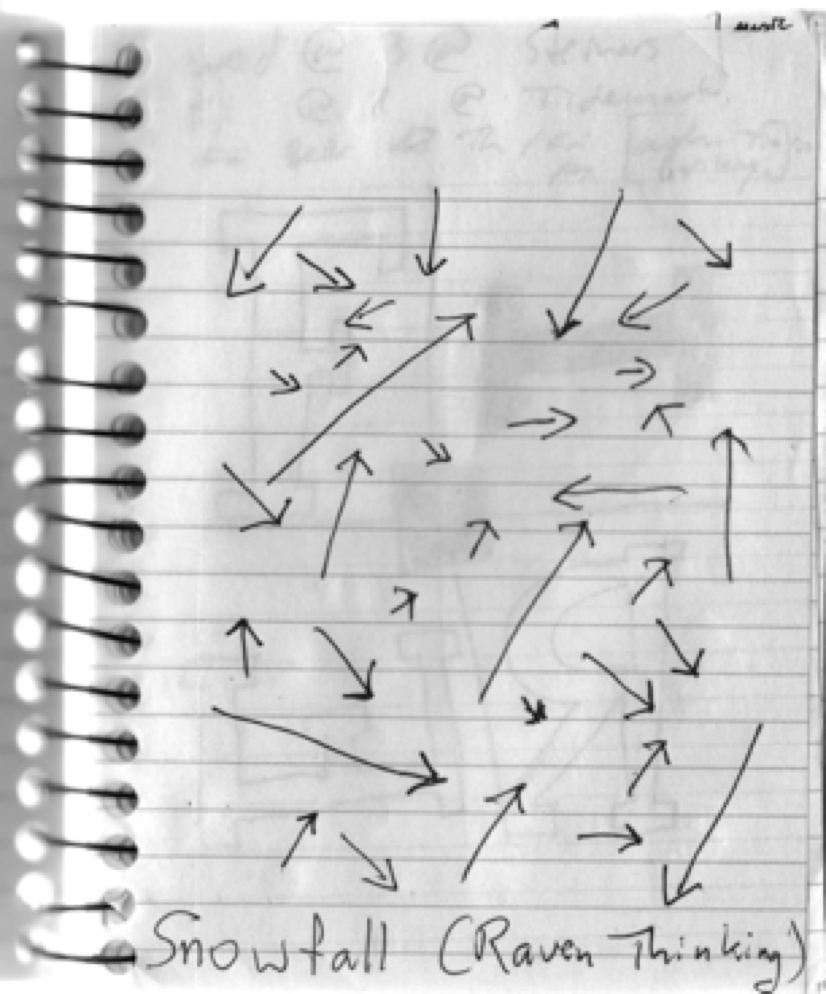

Well, that was fun, so I turned the page. After all, it had started snowing outside…

… with big wet flakes coming down sideways and swirling around any building that blocked it:

It went on like that for days, with the raven tracking me up the canyon in case a) I dropped a sandwich, b) slaughtered a sheep or c) lost my footing and became lunch…

… and exhausted at night, full of a language I could only understand peripherally, but which was taking over my mind and settling it out in a new shape. Eventually, it became a game of Where’s the Raven Now?

The answer was in plain sight, of course, but had to lead first to its natural conclusion through the path of self-negation. So, you guessed it, more math, like this:

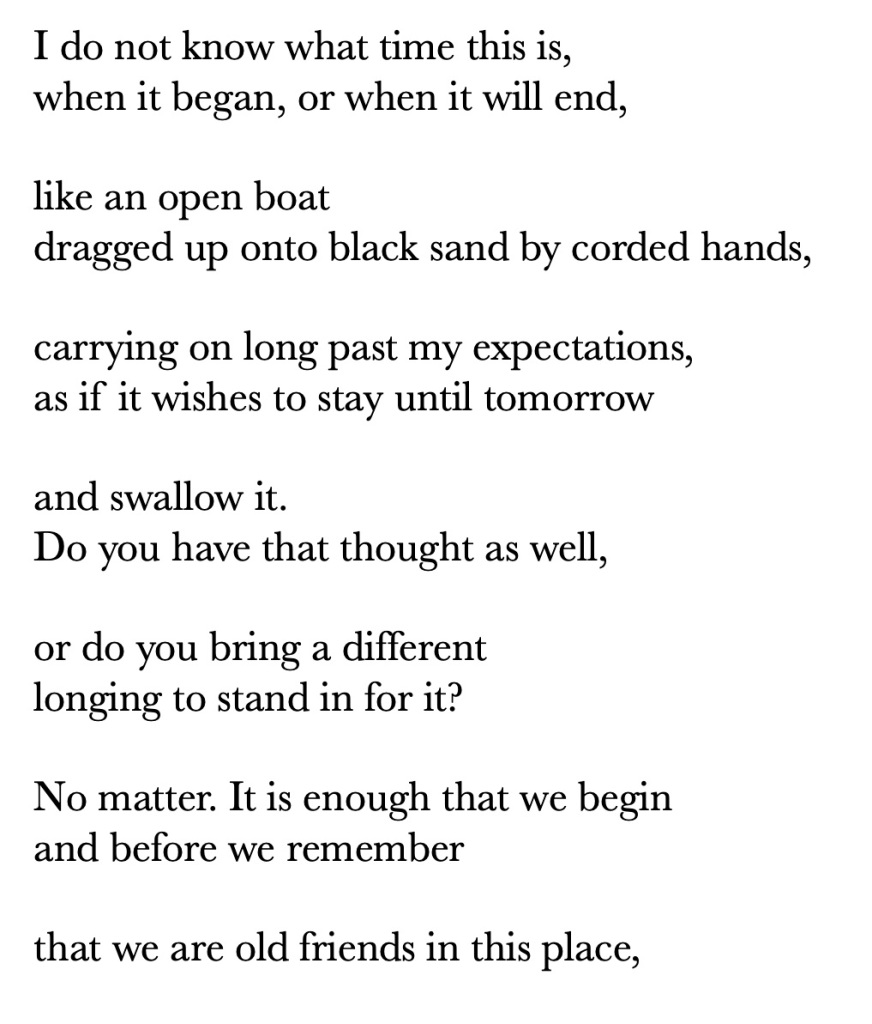

And I left it like that. My time in Iceland had run out. Still, I came back three years later and this time, in my exhausted evenings, travelling around the country, I wrote poems in words (of all things!) at night and, look at that, essentially they were the same poem as the visual artifacts from the trip before, except my English had become closer to Icelandic, elemental, like this:

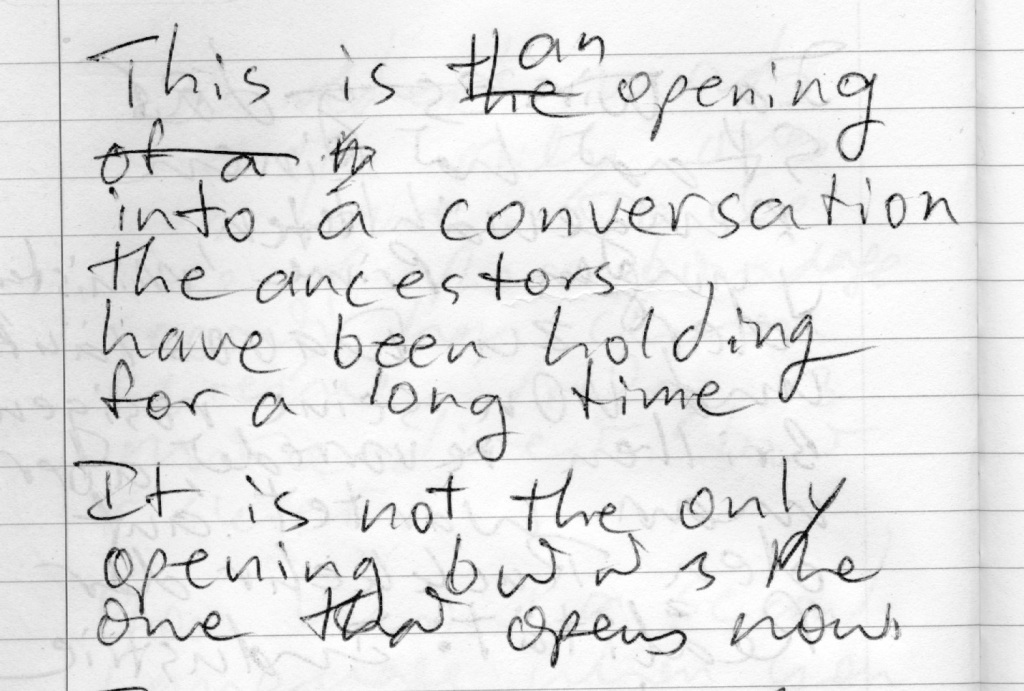

There’s more than one way to poetry. Some, like this, lead away from poetry to the world, and find their mind, and self, there. It’s a place almost wordless, as Icelandic began for me, but not quite. Physical things are words there, just always on the edge of understanding and quickly flying beyond it into presence, not just of those living today but of those who have woven Earth and words for a thousand years and more. Here’s how I first put after I came home, if one can even leave such a place to go to another:

Photographs can’t quite pull this weaving off, but poems can, because they’re written by reader, writer and Earth at the same time. The path we walk today, whether it’s across a mountain’s back or through a poem, stretches back generations.

Such is reading a poem, too, especially with poems like those in Landings, which are the Earth and a compass at the same time…

… waking together as an island and an eye.

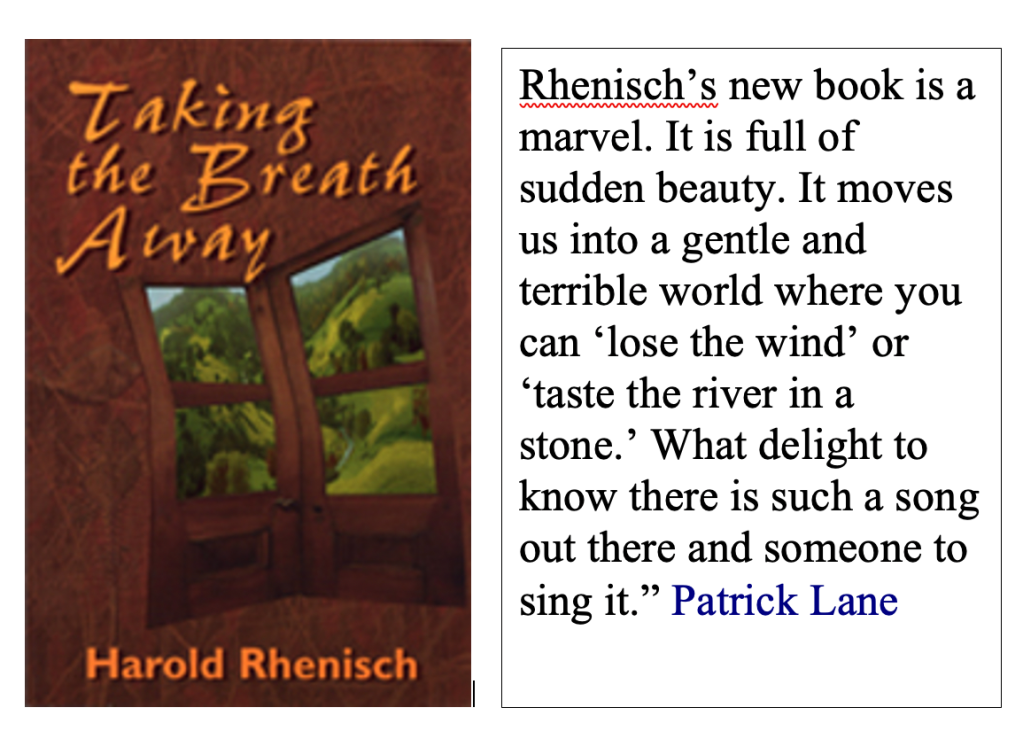

Until the New Year, if you buy a copy of Landings, I will throw in a free copy of my book of German travel poems, Taking the Breath Away, for $30, postage included in Canada. That’s a $48 value. As the poet Pat Lane said of Taking the Breath Away

Landings: $20 + Postage $14 + Taking the Breath Away $14 = $30.

A Review of Landings, Poems from Iceland, in The Ormsby Review

Today brings Luanne Armstrong’s review of my new book Landings. Thank you, Luanne!

It’s fascinating to see my book make her way out into the world like this! And Luanne picks up on a theme that slid right past my attention, the close relationship to this book and my CBC Prize-winning poem “Saying the Names Shanty.” You can read it here on the long-list for the prize: https://www.cbc.ca/books/literaryprizes/saying-the-names-shanty-by-harold-rhenisch-1.4371756.You can read the story of the poem in the post I made when it was short-listed: https://haroldrhenisch.com/2017/11/08/saying-the-name-shanty-nominated-for-2007-cbc-poetry-prize/ And now Al’s great poem is alive again in Iceland! That’s not bad for a bunch of Canadian poets! Thanks, Al.

You can buy the book here, or order it from Audrey’s Books or SaskBooks. See? You are just a click away from the eagle troll guarding Arnarstapi (Eagle Sea Stack) Harbour.

And since we’re talking names here, one lovely thing about Icelandic is it’s English with an old twist (or English is really bad Icelandic.) It goes like this:

Arnarstapi:

Arn = Ern, the old word for eagle (eagle and eyrie both come from ern)

-ar is a grammatical connector, much like the ‘s in “eagle’s.” (But not quite.)

Stapi = Staple, in the sense of the little bent piece of metal that holds paper together. It seems odd, but the dear little thing is really named after the pile it holds, which is a stack. (In German, it’s simple. A stack is just a staple, and that’s that.) So, it’s a stack, a geological term for a stranded piece of a sea cliff, eroded away from behind.

So, yeah, Eagle Sea Stack, or Arnarstapi.

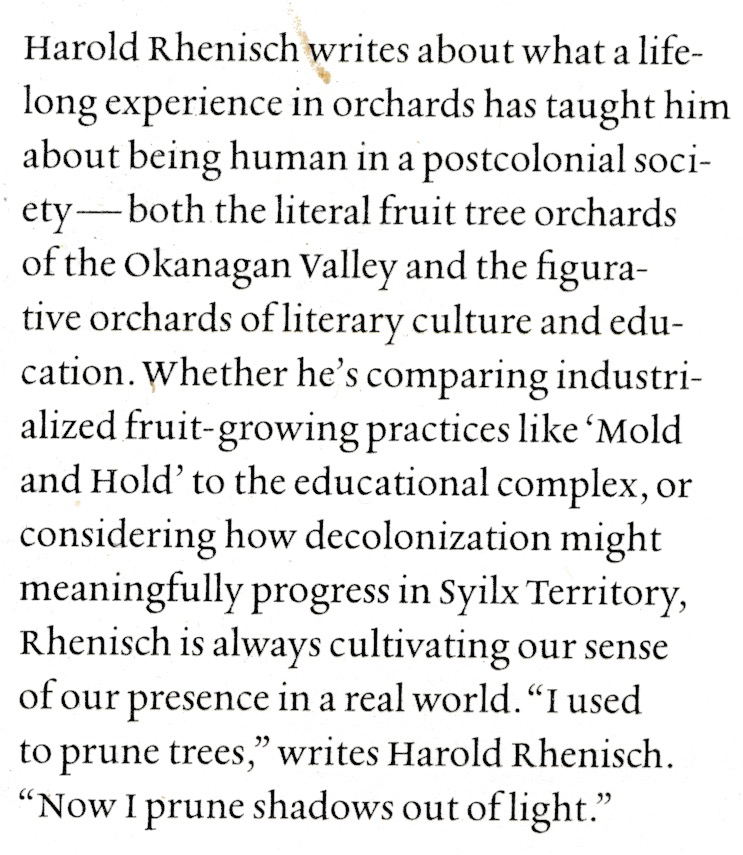

The Tree Whisperer: My New Book on the Poetry of Tree Pruning

This is a beautiful book, that holds 51 years of my personal tree pruning experience, and a few thousand years of ancestral experience behind it. This hand-made book is just out from Gaspereau Press.

And about 55 years of conversations with my father about trees and the world. This is a book close to the heart. Look at what this blog has given us to share.

Isn’t that the truth. Fruit tree pruning is not about shaping a tree, nor is it about dominance. It’s about making space for light. One is really making a path for the sun. Trees will follow that. So do I.

Forty-seven years of poetry are in this book as well, and close to sixty years of experiences with the Earth, as she has raised me and sent me on, from the industrial orchards of my childhood and youth, to my work today, rebuilding lost Indigenous orchards, one graft at a time. This spring, I pruned a transparent apple tree for a bear, even. That was the deal.

years, as bears, horses, human traders, bluebirds…

..and my family, the Leipe’s, the tree people, have brought old knowledge forward into the present.

hem before I learned to write poetry. Unsurprisingly, when I started to write poetry, I was really pruning trees. This book is the story of that path. Its insights into poetry, and tree pruning, come from a deep path, in a sculptural art form in which one must see into the future through the body of another living creature, and work with her to help her thrive.

The Tree Whisperer: Writing Poetry by Living in the World is in the tradition of Henry David Thoreau’s essay Wild Apples, which he wrote after the Battle of Shiloh during the U.S. Civil War in 1862. It was a book about the apples he loved, as is The Tree Whisperer…

Such as grow quite wild, and are left out till the first of November, I presume that the owner does not mean to gather. They belong to children as wild as themselves,—to certain active boys that I know,—to the wild-eyed woman of the fields, to whom nothing comes amiss, who gleans after all the world,—and, moreover, to us walkers. We have met with them, and they are ours. These rights, long enough insisted upon, have come to be an institution in some old countries, where they have learned how to live. I hear that “the custom of grippling, which may be called apple-gleaning, is, or was formerly, practised in Herefordshire. It consists in leaving a few apples, which are called the gripples, on every tree, after the general gathering, for the boys, who go with climbing-poles and bags to collect them.”

Henry David Thoreau, Wild Apples, 1862.

us in this conversation, as you have joined the 153,000 visitors to this blog, because this is a book about the environment, cultural reconciliation, education, poetry, our common past and our common future. In 1937, my great grandfather gave my father a garden …

Hopefully, a long way. You can order The Tree Whisperer from a bookstore, or click on my button on the top of this page and I’ll personally send you a signed copy, with my blessings.

A Journey Through a Poem: A Gift for You

This fall, I will be completing a guide for poets, readers and writing teachers, to illustrate the techniques of my new book Landings: Poems from Iceland and guide you into its language. This is ecological poetry, in many forms. I’d like to share a draft of one of these introductions with you today. This one is for my poem, The Way Home. I’m hoping this guide will help pass these techniques on and illustrate some old techniques of poetry in new love poems. Each gives some background to the poem, discusses some of the techniques that power its shape and help it achieve its effects, and presents a few exercises for practice and enjoyment (I hope!) The Way Home is a circular poem. The discussion begins with the Old Norse concept of world, a spherical space. You can get a glimpse of it in the mouth and eye of the ogre below, on the Arnarstapi shore,

The guides will discuss everything from Old Norse’s influence on English as an Environmental Language to the psychological roots of elves, and from the use of couplets, double rhymes, cross-stitch chiming effects, pass-it-on rhymes, to oral effects on the page, kinetic verse and symbolism. You can download the file below. There are 16 pages in the full file. This one discusses the journey words make from the throat to the lips to the ear, and the use of soft rhymes following hard internal chimes and rocking wave patterns to shift the emphasis of language away from reportage to embodiment.

Also, the poem is about coming to the edge of the known world… and then going further. For that, the full poem, in the book, is just the thing:

The King of Atlantis and You

Consider him looking over our shoulder in Reykjavik while we read Landings: Poems from Iceland, on a morning after snow.

A century ago, the myth was strong in Iceland that it was part of the lost continent. Gunnar Gunnarsson, the novelist in whose house much of the book was written, even took a cruise there in 1928. That’s three landings, I think: Gunnar’s to the Canary Islands, mine to his house, Skriðuklaustur, and this crowd’s on the Icelandic shore:

The Way Home

Let me show you a few pictures from Iceland, to illustrate the introduction to my new book Landings: Poems from Iceland. First the introduction. I call it The Way Home.

We are in the open Atlantic. Every poem about to open before you springs from a place and bears its name. At each of these wells, the earth speaks through human and animal life. Flowers bloom and knock around in the wind. There is always wind.

And just like that, you are in an island in the North Atlantic. In his great anti-war novel The Shore of Life, written in anguish immediately after the Battle of the Somme in World War I…

… Gunnar Gunnarsson noted that the land is ringed with a deadly surf, that one must cross, either for fish or for the world, and must cross back home again for shelter, I think he had Iceland’s eider ducks in mind. Look at them here in Neskaupstaðir, fishing with their chicks in the surf.

Some of the chicks get tossed a metre into the air, and then dragged down a metre under the waves.. If I’m right, this is Gunnar’s image of World War I. So much has gone into portrayals of its butchery and horror and senselessness, yet to deal with his own horror, Gunnar chose an image of life, and one at the heart of the Icelandic soul. That choice is at the heart of this book, too. This is a book of hope, and of coming home. As I point out in the introduction…

1100 years ago, Icelanders settled this volcanic island in the middle of the ocean. The place is not so much a land as a landing, that moment when the keel of a boat hits shore and is lifted and held up, suddenly solid and free of the grey sea.

The days of going out into the open ocean to catch a few low-value fish are over, yet the knowledge gained from the experience remains, and has found its way into words here.

These poems are the moment when the land lifts you up: not an object but an energy and a process. Here’s a central passage from my poem “The Meeting Place”, one of the book’s Landings:

As speakers of English, we are all home here in Iceland. Landings is a map. It’s not in bookstores yet, but I’ll get you a copy. I have a few maps, too. Just ask. Drop me a line on Facebook, at www.haroldrhenisch.com, or @hrhenisch. We’ll be talking soon.

My New Book Has Landed!

A decade-long love affair with Iceland fills my new book with poems and prayers that are lifted by place and magic. This is a book for people who love the Earth, told in a language physically anchored to the roots of English in the old sea-going North.

It is also full of trolls, elves and other land-based understandings of consciousness the Norse brought from Norway 1100 years ago. In Iceland, even a man or a woman could become a troll, even while living, as the word originally described only the relationship of a person to a specific place. Only? Well, it’s a lot! Here’s one of my favourite haunts.

It is always good to know where the neighbourhood volcano is.

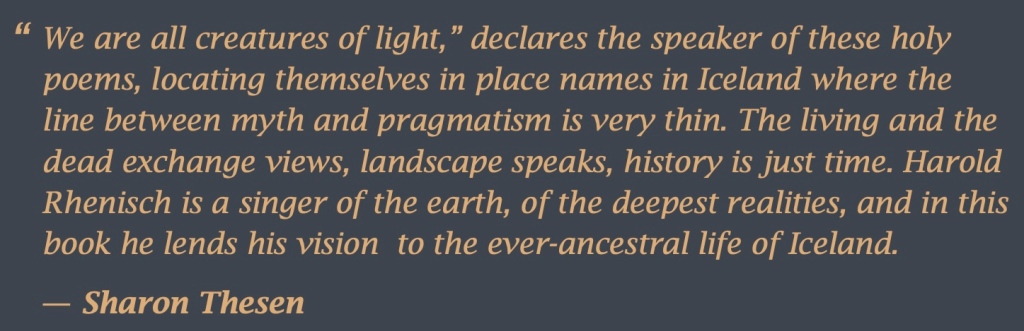

Here’s how Sharon Thesen describes the book:

It is, as you can see, a work of love. The “Landings” of the title are those moments when the earth lifts up the keel of a boat and holds it steady, where just a moment before it was rolling at sea. It is an energy that precedes “land” and more accurately describes human relationships to it. In other words, it is a book about being home on the Earth, and is the culmination of decades of work exploring the roots of English to function fully as an indigenous language. Here is Petursey, Peter’s Island, one of the elf cities of the Icelandic south.

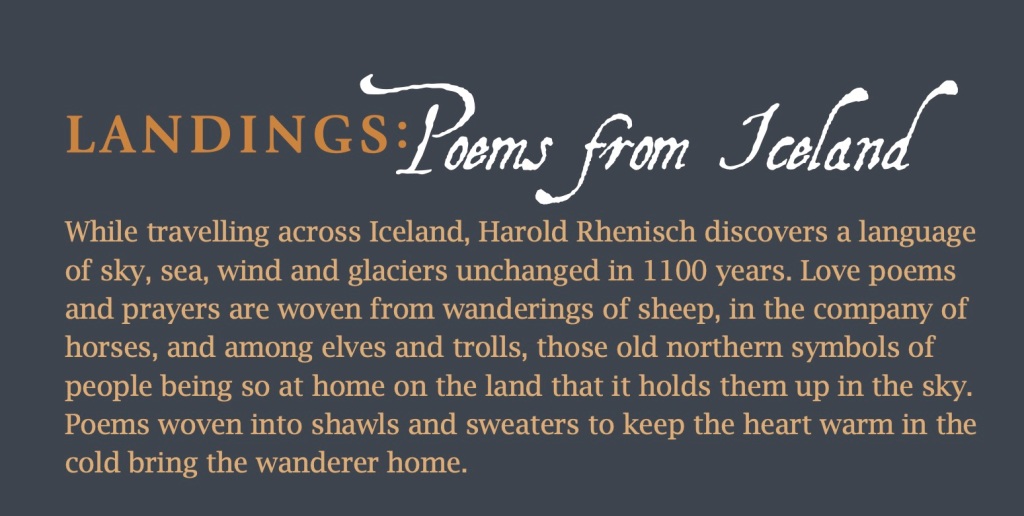

These are simple poems of wit, grounded in experience. They come with a rich glossary of names, giving the story of each place in which they are set. As the publisher says:

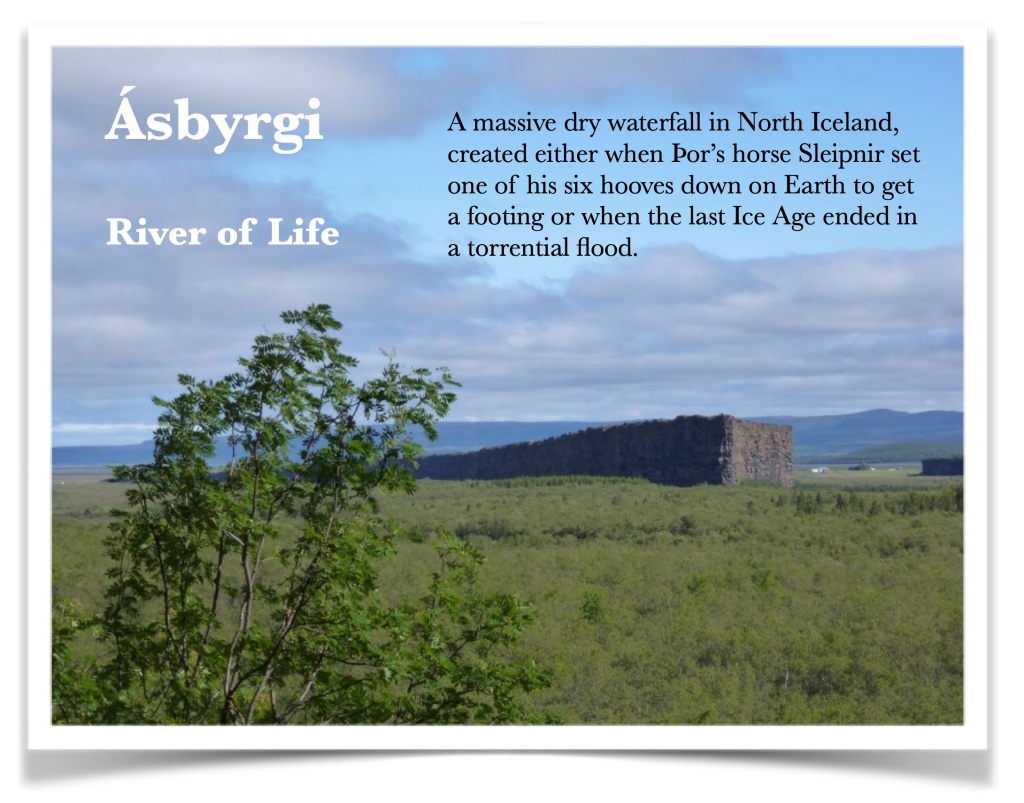

Here’s an example from the glossary:

Hallormsstaður / Hawthorn Farm

This old parsonage houses a children’s art school within an arboretum of exotic trees from the global North, and a guest house in the dormitory of a girls’ boarding school, where the girls of the district were taught Icelandic embroidery as part of the project of freeing the country from Denmark. It worked. Never underestimate embroidery.

I spent a month just up the fjord as writer in residence in 2013, talking to the local thrush. Here’s Ljósárfoss, The Waterfall of Light, in the Birch and Hawthorn Forest the girls embroidered a country from:

And the embroidery? You can tromp through the hills and still pick these flowers today. The poems in the book are like this, too, following sheep and farmers through the heather and the grass.

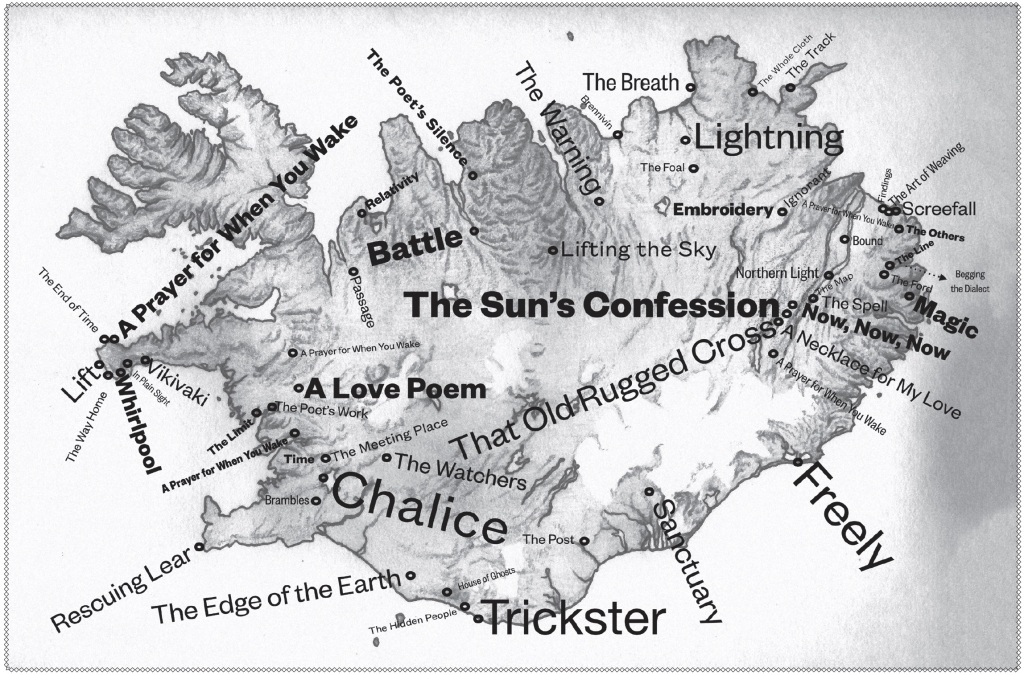

In addition to a textual table of contents, the book’s frontispiece is a map as well, showing the whole country as the book.

Thanks to my editor, Daniela Elza, for urging us to make this deep ecological guide.

Those girls are one of my inspirations. The book is a woven artefact, like the lines that sheep make wandering through the Icelandic summer, which are spun and knitted again into the charms we call sweaters to keep us warm together in the winter dark. Here’s how Patrick Friesen describes this approach:

This is the poem craft I have learned after forty seven years at this game, written out of love and in honour of all that Robin Skelton taught me of poetry, magic and the weaving of silence in among words. This is not a poem of the past, though. Its songs are of the present and the future, physically grounded. It’s not just the horses grazing on the old turf house ruins at Eiðar, the farm called Fate, that stretch across a line of verse but don’t break it…

… but words as well. Here is the ending of my poem Findings, contemplating the Syrian exodus from the lost harbour of Stapavík in the Icelandic East.

Here’s the view from the Stapavík Trail, looking north over black sand and the dunes of the bird sanctuary between the Seal River and the Glacial River itself.

The beach, though, is not for humans, and that’s about right.

These are poems for living voices. Here’s how Marilyn Bowering describes them:

In this time that seems to want to drive people apart from each other and the land, I found myself in Iceland, writing a book about coming home to a renewed Earth and feet solidly standing on it. Sometimes those are the feet of a thrush, those curious birds that follow you around, stare you in the eye, and always on the verge of speech.

This is the work of a poet, as I know it. Here’s the first half of my poem “The Poet’s Work.”

The first half of writing this book was to build a musical language of spirit embodied in the Earth. The second half is to share it with readers and listeners. Thanks to my publisher Byrna Barclay of Burton House Books, for finding the love poems in my travels and bringing them into print for us all. The best way to buy this book in these strange times is from me, or from Burton House. Or order a copy into your local bookstore, and gently suggest that we do a reading together.

And, please, be in touch. We’re open to any ideas as to how I can bring these poems to voice and ears and keep us all close as we start to heal our broken Earth, one word and one landing at a time.

Let’s talk soon. Here’s the book details your store will need.

Entering the World in Joy

In 2003, I wrote a series of 365 poems in 6 weeks. The series included several of my poetry books, including my favourite, The Spoken World (Hagios Press [Radiant] 2011). As no one has seen that book, or the speech between the living and the (so-called) dead, through the gates of love and Earth, here’s a small spell for stepping into the Earth’s embrace, that seems to have been written for these times.

Blessed be.

© Harold Rhenisch 2015

There’s more, here: The Spoken World.